The Restoration of the Henry Street Settlement Exterior Ironwork

By Christine Lyons, written for Spirit Ironworks, Inc.

New York City’s architectural structures offer us a visual narrative of the city’s compelling and dynamic history. As traditional craftspeople, we recognize the significance that these structures have within the edifice of our societal fabric and to our sense of memory. We understand the need to preserve such framework by using careful and thoughtful restoration practices. We believe that it is imperative to maintain as much of the original material as possible so that each piece can retain its historical integrity. No such project epitomizes these values as the Henry Street Settlement exterior ironwork restoration project. The project began in the fall of 2018 with funding from the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and the Landmarks Conservancy.

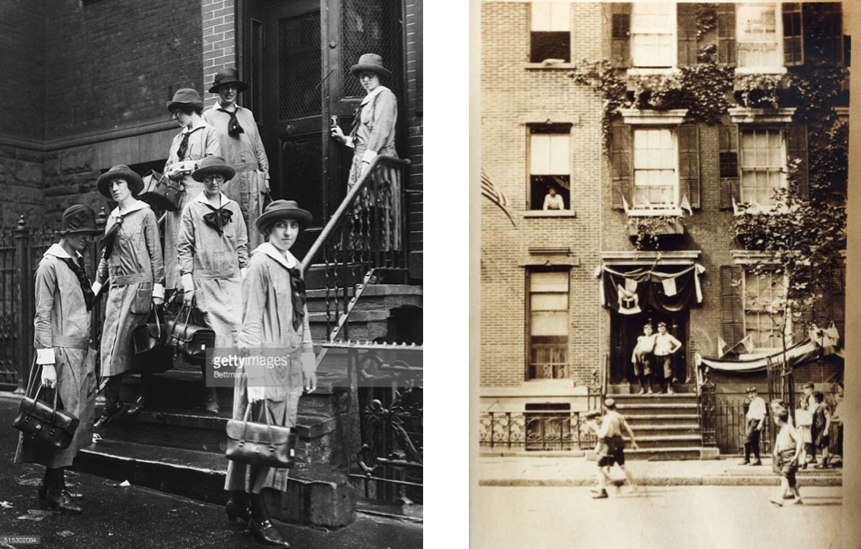

Henry Street Settlement is a nonprofit health care, arts, and social service agency located in the Lower East Side neighborhood of Manhattan and serving New Yorkers of all ages. Founded in 1893 by a young nurse named Lillian Wald, it is considered by many to be the birthplace of the social welfare reform movement. In addition to the Settlement’s 18 program sites are its administrative headquarters located in its original buildings at 263, 265, and 267 Henry Street.

History of Structures

The buildings at 263, 265, and 267 Henry Street are Federal Style row houses that were built in the late 1820s to early 1830s. To date, their original architects remain unknown. Initially, these structures served as private homes for well-to-do merchants and their families. By the mid-19th century, most of the wealthy residents in the area had moved out of the Lower East Side and into the upper areas of Manhattan, and many of these structures were turned into tenement buildings to house the growing immigrant population settling in the neighborhood. By 1966, the New York City Landmarks Conservation Commission had deemed all three of these buildings as historic landmarks. Not only does each building hold great historical value in the cultural development and heritage of the area, but they all retain many of their original 19th century architectural features. These features include the ornate, Federal Style exterior ironwork found at the front of each building.

Site Survey and Assessment

Our first process was to travel to Henry Street and carefully inspect the almost two-century-old ironwork outside the three buildings. We photographed site conditions with the original ironwork in place and used the photos as references when researching and reviewing historical images of the ironwork. The photos also allowed us to create a survey of the site’s current conditions. During the assessment, we examined the ironwork and observed that all of it was made from a mixture of genuine wrought iron and cast iron. Wrought iron is the forgeable ferrous material made until about the mid-20th century and has since been replaced by mild steel. It is characterized by its composite nature, which is fibrous like wood. It was originally called “wrought” to distinguish it from cast, or poured iron, because its creation required extensive forming under power hammers and through rollers. Sourcing wrought iron for any restoration can be challenging as it is no longer commercially manufactured.

Featured above: Hand-forged scrolls made from genuine wrought iron and decorative floral motif railing inserts made from cast iron.

Removal and Cataloging

Once the site was surveyed and the initial assessment completed, our next step was to travel back to the site and carefully measure and remove the damaged ironwork. Each section was then brought back to our studio, cataloged, and prepared for paint removal.

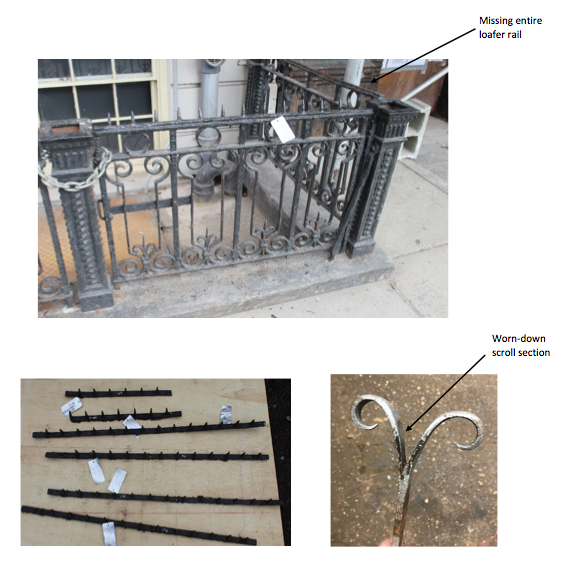

267 Henry Street: Loafer Rail Damage Assessment

The damages to the original loafer railings sections were extensive. We removed five sections in need of restoration. The top bars were badly bent out of shape, and some of the spikes were either damaged or missing. In addition to the five sections, we noted a railing section whose spikes were entirely removed. This section was particularly interesting as we noticed that the bottom fleur de lis scrollwork was quite worn, illustrating that it had bared both weight and friction for some time. It became evident that the spikes had been purposely removed so that people could sit on the railings while the scrolls were used as footrests.

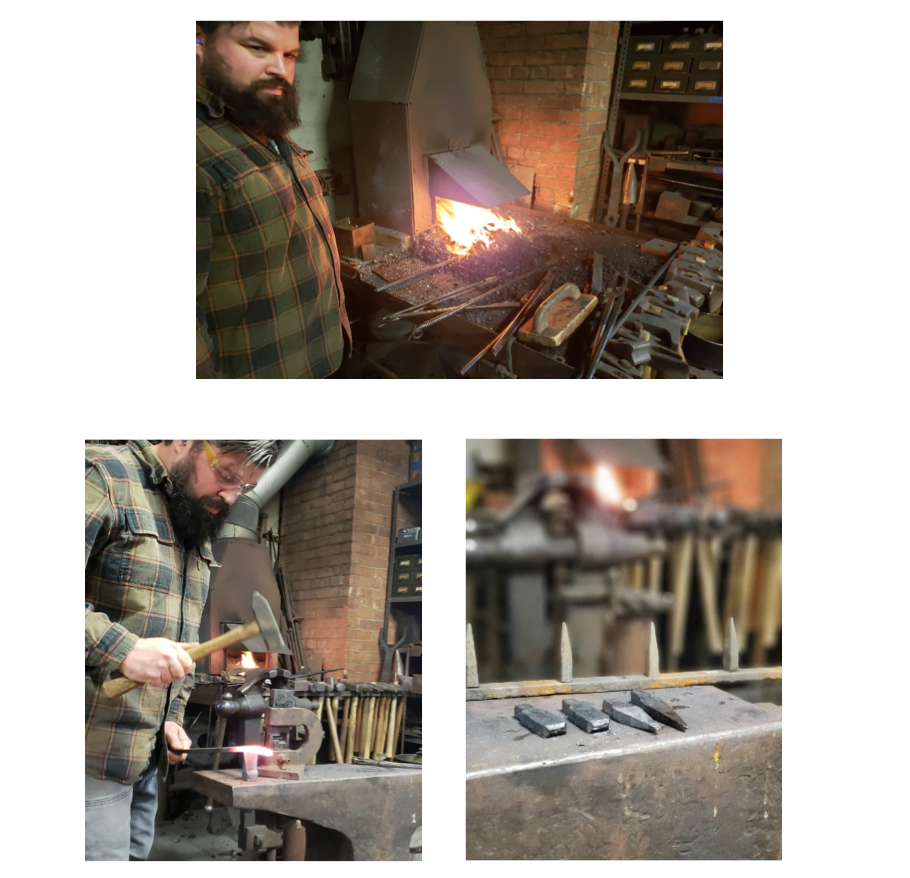

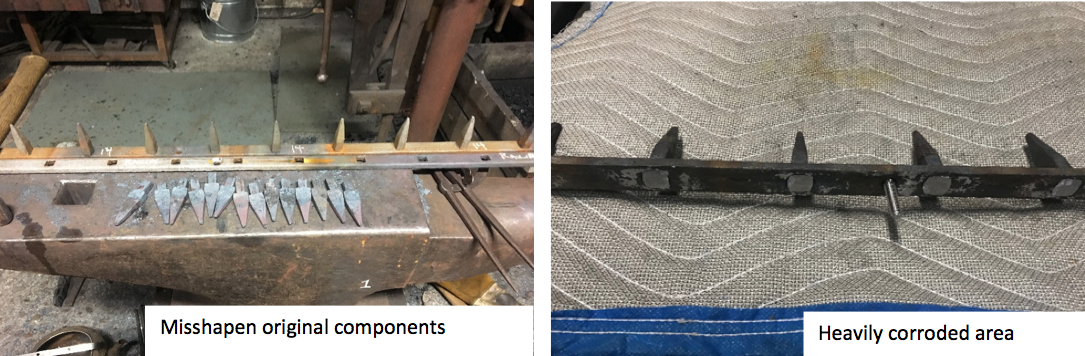

267 Henry Street: Loafer Rail Restoration Process

The restoration of the loafer rails outside of 267 Henry Street was an involved process. The initial step was to straighten the badly bent top bars by heating them at our forge and straightening them with a hammer. The missing top bar was remade using reclaimed genuine wrought iron that was forged and hammered to match the style and dimensions of the existing pieces. The missing spikes were also remade using genuine wrought iron. The images below illustrate this process. They show our blacksmith cutting and shaping each spike to match the original forms. Once made, each spike was passed through the openings of the top bars and forge welded into place. This method of recreation was very much in line with the original method of construction during the 1830s.

267 Henry Street Damaged Fencing Panel Assessment

During our initial assessment, we found the railing panels outside of 267 Henry Street to be mostly intact. Though quite weathered, the panels still displayed the artistry and craft found in 19-century American ironwork. Although the panel sections were missing few parts, the components throughout the design were badly bent and misshapen. These included the horizontal and vertical lines that make up the framework structure of the fencing sections. In addition to the warpage, much of the ironwork showed signs of rust and corrosion caused by many years of exposure to outdoor elements.

Restoration of Fleur De Lis Components: 267 Henry Street Progress Images

The fleur de lis components were made up of three pieces of genuine wrought iron, which were forge welded together. Forge welding is the oldest form of welding. The pieces to be welded are heated to their near melting point and then hammered together. The images below illustrate the replication process of the fleur de lis. Our smith begins by forging a piece of reclaimed wrought iron into a bar. The bar is then cut into three pieces, their tips hammered into points, and partial curves formed to resemble the leaves. A tenon is formed on the end of the bar using a guillotine tool. The tenon will go into the existing hole in the bottom rail (mortise) with the end peened over to lock it into place.

267 Henry Street: Restored Fencing Section

Below is an image of a restored fencing section, before it receives its final rust-proofing and paint applications. All the rust has been removed, and deteriorated areas have been repaired or replaced. The distorted curves found throughout the scrolls and bottom fleur de lis components have been reshaped back to their original flowing appearance. The craftspeople of this era were much more concerned with the beauty, harmony, and appropriateness of the design than with the precise regularity of the finished product. It was the hands of these very artisans that made each piece so special.