School Nursing Celebrates 120th Anniversary

By Mataeo Smith

More than 100 years ago, nursing pioneer and activist Lillian Wald, with her nurse colleagues, philanthropic partners, and others, set out to transform health care and create a network of social services for residents of New York City’s Lower East Side and, ultimately, the entire city. Today, one of Wald’s key innovations—school-based health services for children—are taken for granted as a prominent part of the health care ecosystem for school-age children. Wald spearheaded this effort to reduce student absenteeism, starting with an experiment that led to widespread reform of care for sick children across the nation.

Prior to Wald’s intervention, children of low-income families in New York City were susceptible to diseases that consistently kept them home from school. Of equal concern: the children of hardworking families often attended school with contagious conditions. Many of these children lived in the tenement district, which was home to some of the poorest immigrant families in the city, with little access to medical services. Unsanitary conditions in school classrooms only exacerbated the issue. An investigation by the New York City Department of Health discovered that children with contagious diseases like measles, diphtheria, and scarlet fever were crammed into sweltering and overcrowded classrooms (Houlahan, 2018). Subsequently, the city put forth a new system that made compulsory the medical inspection of all school children by a physician. The measure was made in vain, however, as sick children received no treatment and were simply excluded from school; some never returned (Houlahan, 2018).

Wald’s (1915, p. 46) impetus to reform school health services stemmed from a personal encounter with an illiterate 12-year-old boy named Louis whose absence from school was attributed to not being able to “cure his head.” As she described in her memoir, Wald (2015, p 47) determined that he had a treatable case of eczema. Louis’s mother had been worried about her son’s future, because his despite treatment from several local free clinics, schools had denied Louis admittance. The exchange with Louis greatly affected Wald; she and her colleague Mary Brewster created a list of children who had been excluded from school for treatable medical reasons (Wald 1915, p.48). Similar to Louis’s, most of their conditions were amenable to nursing interventions. Wald couldn’t fathom the thought of a treatable disease impeding a child’s education. At her suggestion, a one-month school nurse experiment began in October 1902.

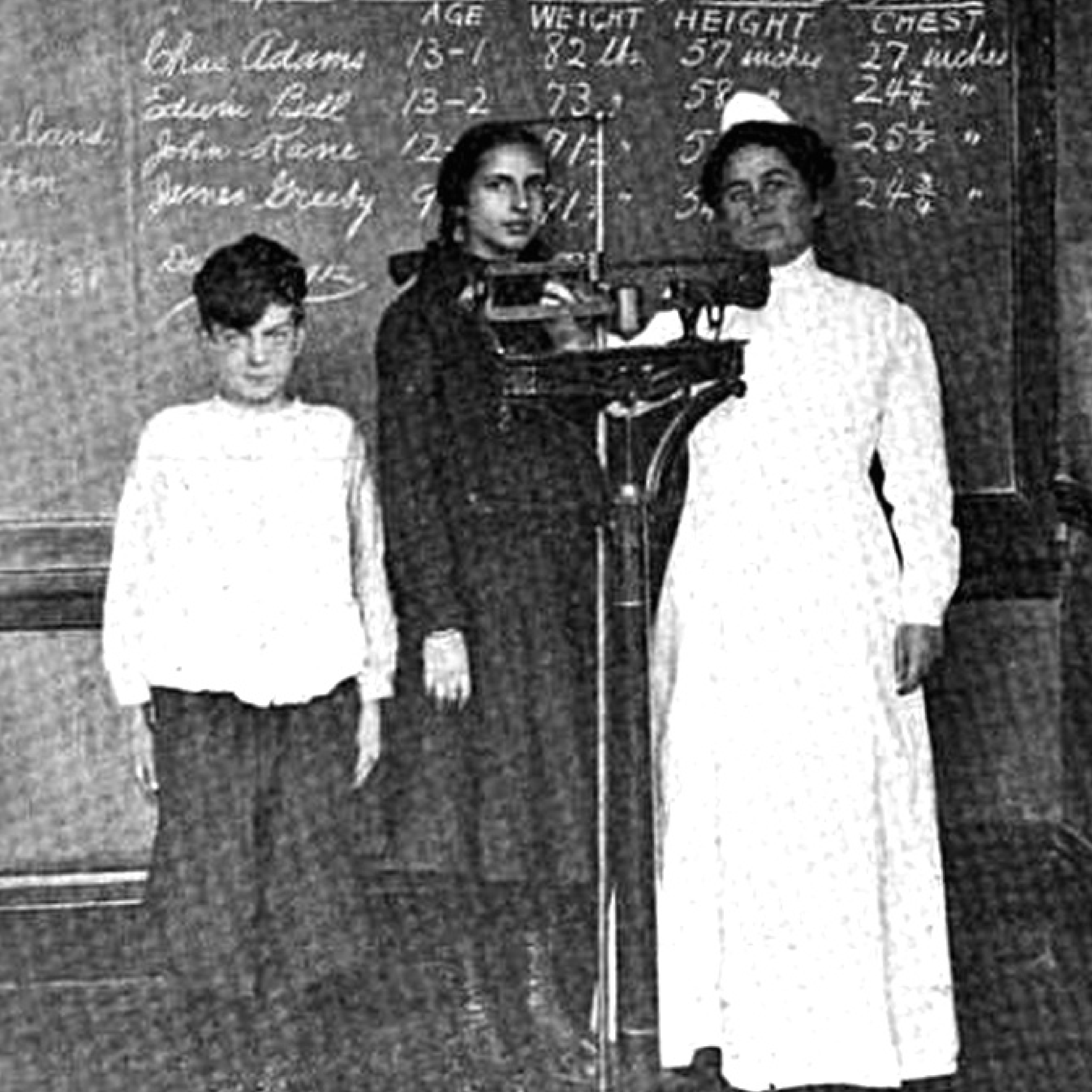

Pictured: Lina Rogers, the first school nurse placed in a public school in the U.S.

Wald—aware that nurses were placed in British schools—offered the services of one of the Settlement nurses, Lina Rogers, for the experiment because of her expertise in pediatrics (Houlahan, 2018). Roger’s main objective was to keep the children in school. For two months, Rogers, on her own, cared for students across four New York City schools, whose combined enrollment was 10,000. Space was minimal: In one school, she treated students in an unused stair closet (Houlahan, 2018). In just the first month, Rogers treated 829 students and made 137 home visits (Houlahan, 2018). Rogers not only treated the children but taught families about health promotion and disease prevention. During home visits, she provided families with a means for ongoing health care and advised them on ways to keep their children and homes clean. Rogers officially became the first municipal school nurse on November 4, 1902, launching a permanent position within New York City schools (Houlahan, 2018).

This October 2022, The National Association of School Nurses (NASN) and Henry Street Settlement celebrate the 120th anniversary of school nursing in the United States. The NASN began in 1968 as the Department of School Nurses (DSN) in the National Education Association. By 1979, the DSN became their own incorporated entity as NASN. Its goal is to boost the ability of every child to succeed in the classroom and advance the quality of school health services. NASN continues to champion school health, develop educational programs through partnerships with national health organizations, and advocate for school nursing services among stakeholders. To advance 21st century school nursing practice, NASN provides school nurses with clinical practice guidelines, toolkits, education programs and modules, manuals on care coordination and addressing chronic absenteeism. School nurses continue to work with students and families to promote health, prevent disease, advance health equity, and develop partnerships so that students can learn safely and in good health.

Henry Street Settlement today continues to provide social services in New York City public schools. The organization operates 11 school-based mental health clinics on the Lower East Side, provides afterschool care in five schools and two local community centers, and runs both a preschool and college preparation program. In keeping with the Settlement house model of meeting the needs of individuals, families, and communities, the teams working in each of these settings seek to meet all aspects of their student families’ needs, referring them to assistance both inside and outside of the organization for health, educational, financial, nutritional, and other social support.

References

Houlahan B. (2018). Origins of School Nursing. The Journal of School Nursing. 2018;34(3):203-210. https://doi:10.1177/1059840517735874

Wald, L. (1915). The House on Henry Street. Accessed at https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_House_on_Henry_Street/An_aAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover